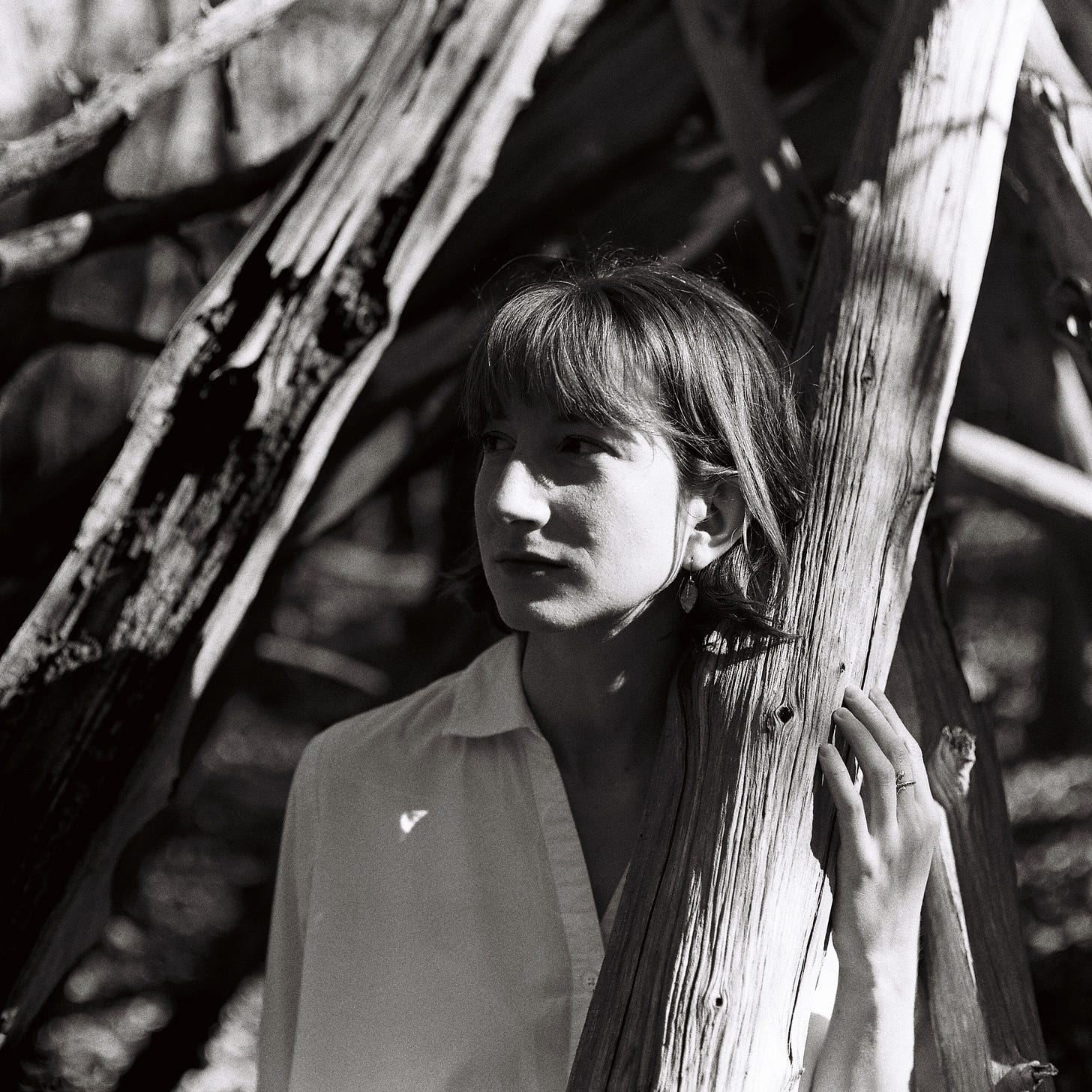

Happy Father's Day + Q&A with Emilie Menzel

Sweet Lab intern Marina Escandell-Tapias interviews poet Emilie Menzel.

Happy Father’s Day, if you observe. It’s a hard day for some and an easy day for others. Years ago, I wrote an essay, My Father the Heartbreaker, for The New York Times. This led to more essays: How I Finally Discovered My Late Father’s Vulnerability (The Girlfriend), Writing About My Father (Brevity), The Unexpected Benefits of Divorce (The Girlfriend) and What Do You Owe a Parent Who Was Mentally Ill? (The Ethel). This came after devoting roughly half my memoir, Sweet Survival: Tales of Cooking & Coping, to trying to understand my father.

Photo illustration by Barbara Gibson

I know being a loving father is not easy, especially if your father was difficult, absent, or abusive. My father is gone now 20+ years, and in his absence, I have come to appreciate him in new ways by rereading his letters, journal entries, and emails. Writing about him has been healing and instructive.

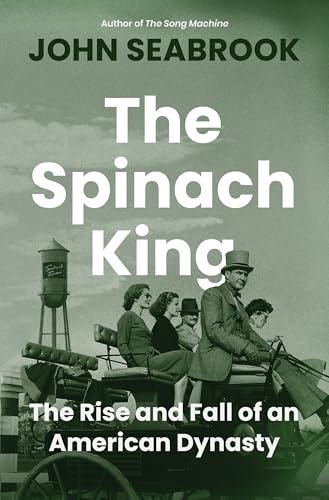

Last week, I listened to a great New Yorker podcast with David Remnick and John Seabrook. Seabrook has a new book out, The Spinach King: The Rise and Fall of a Family Dynasty, which examines the huge frozen vegetable business his grandfather built and the subsequent rift between his grandfather, father, and uncles, which resulted in a lawsuit. Seabrook relied on his father’s business diaries, pre-trial documents, and more than 50 interviews with people who knew his grandfather to write the book. Seabrook describes the story as “ ‘Succession’ with spinach.”

The interviews portray my grandfather, enfeebled by old age, as an addict, a predator, and a paterfamilias who seemed to hate his own flesh and blood. Having left this material for his writer son, my father must have wanted the true story told, even if he couldn’t bear to tell it himself. - John Seabrook, The Spinach King: The Rise and Fall of a Family Dynasty

My father-in-law passed away in January, and I am grateful beyond words that he raised my husband. The first Father’s Day without a father or the father of your children can be extremely rough. If you’re one of those people who felt or feel unconditionally loved by your father, consider yourself lucky. To everyone else who has a complicated relationship with their fathers, ex-husbands, ex-partners, and fathers of their children, come write with us at Sweet Lab.

❖ ❖ ❖

In other news: I’m reading How to Lose Your Mother: A Daughter’s Memoir, Molly Jong-Fast’s juicy and delicious book about life with her mother, Erica Jong, author of Fear of Flying, among other things. The memoir discusses alcoholism, narcissism, fame, cancer, sobriety and the challenges of being the child of a writer. It’s hard to put down.

I realize this newsletter feels like it is permanently tuned to an all-Wellesley channel, and it is again this week. Our Sweet Lab intern, Marina Escandell-Tapias, did a great Q&A with fellow Wellesley alum, poet Emilie Menzel.

Describe your writing process.

I tend to write a lot through accruement and through scraps, and less so by sitting down in one session and creating a long sequence or poem in a single go. A lot of it is gathering these phrasings and then reshuffling them, or collaging them. I think of it as sewing, like a tapestry. There’s some fun in picking up these phrases and then turning them around, and then moving them. I’m not a painter, but if you’re working with colors, they have different resonances or hues that come through depending on what they’re next to.

When ordering the book, I thought about it as creating a musical piece. I’ll spread everything out on a big table and then pick up sections, read through them, and try to find the tempo or texture that I want. Here’s what I know I want to be moving into. How does this match with that? I read through the sections and bridge them to other pieces, ultimately threading everything together. In this case, I printed out all the stanzas and taped them together. Then I had this giant document, like a big scroll.

From the beginning, who was your intended audience?

I think that’s something I would have considered sooner if I was a fiction writer. When I was doing the initial draft, I was in an MFA program, so I think that very literary atmosphere was probably part of what I was thinking about. But in a lot of ways, I knew I needed to write this, and needed to move through the process of writing it. And I did want it to be kind of on the bridge between prose and poetry. I was thinking about how people who were not poets would be reading it. But also, I tend to worry too much about how others are perceiving my writing. So I feel like I was trying to branch away from that, too.

Tell me about your background.

My dad was an animal behaviorist, and my grandfather was as well. This isn’t everything, but I grew up in a home where animals were talked about in a very rich way, and not in a secondary to people kind of way. They were almost more primary than people. I would say learning about people was, as a kid, very similar to talking about animal behavior. That was the vocabulary of my home. My sister and I would hang out and read the giant mammal encyclopedia. And with the rabbit book–it's working in themes of fable and fairy tale and so animals are, of course, a big part of that. A mentor once said that you should know the metaphors of your life, or key images. I think it changes. I will report back, but animals are definitely part of that kind of vocabulary.

What are your recurring metaphors?

Families, mothers, rabbits. Rabbits for a long time were that kind of image. I’m working on a new book, and it has a wolf character as a protagonist. I’ve been accruing different wolf or coyote imagery.

What was the initial idea that led to The Girl who Became a Rabbit?

I think some of it was an idea about form. I had always felt kind of frustrated working in linear work–it felt like having a pebble in my shoe or something. Like it’s not quite right. I felt frustrated with the limitations of the form, I guess also the limitations of language. The project was doing a book-length poem, doing the gathering and creating a story over space that isn’t a plot-diagramed story.

Playing with rhetoric meant also playing with sections that were more explicitly fiction or fable-like. I was going to, at least, try to be very transparent that this is a story—which is a funny thing. I don’t worry about what is a story when I’m reading a novel someone else has written. But for some reason, that felt very important to me. I wrote archetypal characters. And in the book I would not say this is the fable, and this is not the fable. The parts are all very much connected with one another. So, it was also a project of tone.

In terms of topic, it's a lot about how bodies are observed and move about the world. A lot about femininity, or how we’re told stories about how we should behave by our friends, our families, our partners. You know, some of that we enjoy and some of it we don’t resonate with. I wanted to write a story asking, what if I clear the slate and then build it from scratch?

What does it mean to build the body from scratch?

I would not say it’s starting from nothing. I think that’s part of the challenge. You can’t create a clean, experimental state. You have to try to establish a reading or narrative for your own physicality while still moving through the world with physicality.

There’s a tone, there’s a setting, but it’s not established like a fantasy book. There is a sort of bodiless narrator describing the actual physicality.

Who did you trust with the beginning process? Describe the community behind your book.

My (MFA) thesis advisor and mentor Dara Barrois/Dixon. I had taken a fiction workshop and then had a bunch of draft material for that. I remember I was trying to figure out: where do I go from here? Do I put it back into lines? What do I do with this? I was feeling very frustrated. I remember going to her house to talk more and to get started on putting together some final product for graduation. But I was convinced it was terrible. She encouraged me and was pretty integral in developing faith in the form and in the project. And later I gathered that for myself.

I’d say the most helpful thing, in a lot of ways, is just community through my non-writer friends or people who could talk about the general writing process: this is my life as a writer, and this is what I’m struggling with. And, during the MFA, it might have been like–I’m teaching a lot, I have all these things going on outside of the writing world, and I’m struggling to make it to the page.

What struggles and challenges did you face while writing the Rabbit book?

I find it very difficult to write at all. To take up space. The project was to take up more space. I didn’t reshuffle 20 lines of material to make it look like poetry. That was hard, I felt for a while that I had betrayed poetry in some way by not having the lines. I felt like–can I even call myself a poet? I don’t have that qualm now, but that felt like a significant change.

Another challenge was that I knew I wanted to write a book that was nuanced and kind. I didn’t want it to be–these are the good people, these are the bad people–binary. In that way, it was very important for me to hold multiple truths about stories and that was really difficult for me. I felt like a lot of people I was writing next to gathered a lot of authority and power in those binaries. I don’t want to discredit them, they held anger in a very certain way in their work. I felt like that didn’t match my experience. So, I felt for a while that I struggled to find pieces that were displaying anger or frustration in a less pointed shape. I felt like this less pointed form, for me, was an important part of the experience–that experiences hold many things at once. That this is part of the confusion and the intensity of these experiences.

Emilie Menzel is the author of The Girl Who Became a Rabbit (Hub City Press, 2024), a book-length lyric that won the New Southern Voices Poetry Prize, selected by Molly McCully Brown. Their hybrid poetry has received honors such as the Deborah Slosberg Memorial Award in Poetry (chosen by Diana Khoi Nguyen) and the Cara Parravani Memorial Award in Fiction (selected by Leigh Newman). Menzel’s work has appeared in journals including The Bennington Review, The Offing, and Copper Nickel. They earned a BA in English from Wellesley College, an MFA in Poetry from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and an MSLS from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Originally from Georgia, Menzel resides in Durham, North Carolina.

Liz Glazer Stand-Up: Alice from The Brady Bunch, Everyone Is Gay | The Tonight Show

Dinty W. Moore, Butterflies, Clouds, and Joan Baez: How Mindfulness Enhances My Writing Life (Brevity)

John Seabrook, An Ex-Drinker’s Search for a Sober Buzz (nonfiction, The New Yorker)